I’ve done three or four interviews now in which I’ve been asked about the literary models I used in my new novel Julian Comstock.

The name I generally mention is Oliver Optic—always good for a blank stare.

Now, I put it to you boys, is it natural for lads from fifteen to eighteen to command ships, defeat pirates, outwit smugglers, and so cover themselves with glory, that Admiral Farragut invites them to dinner, saying, “Noble boy, you are an honor to your country!“

That’s Louisa May Alcott in her novel Eight Cousins, describing the sort of books she called “optical delusions.” She was talking about Oliver Optic, who was sufficiently well-known in the day that she didn’t have to belabor the point. Her description of his work is perfectly apt, but the effect it had on me (and perhaps other readers) was the opposite of the one she intended: Cripes, is there such a book? And if so, where can I find it?

I’ve since tracked down dozens of his novels—they were so popular that there’s no shortage of vintage copies even today—and I was so charmed by the author’s quirky, progressive and always well-intentioned voice that I borrowed liberally from it for Julian Comstock. He was once a household name among literate American families, and he deserves to be better remembered.

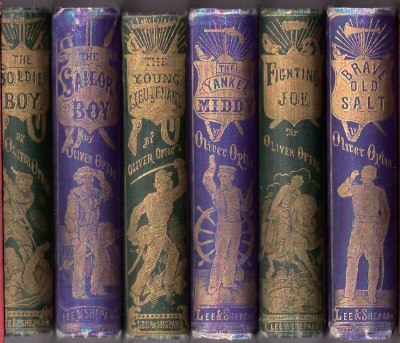

The books Louisa May Alcott was referring to were his Army-Navy series, pictured here. And they’re all you could hope for: breathlessly optimistic stories of train wrecks, steamboat explosions, an escape from Libby Prison, secret codes deciphered, blockade runners foiled, slaveholders defied, betrayals and reverses, etc. etc. You also get Oliver Optic’s weirdly amiable and funny narrative voice—”weird” in the context of the subject matter. The books were written at the end of the Civil War, while the artillery barrels were still cooling and the bodies being shipped home from the battlefields for burial. (There was a boom market at the time for metallized coffins, which made shipping by train more sanitary. Embalming was a new art, often practised by unscrupulous charlatans.)

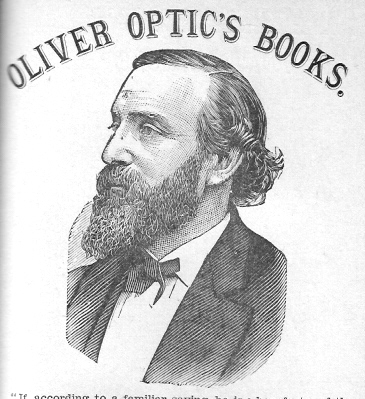

Oliver Optic himself—his real name was William Taylor Adams—was a born and bred Massachusetts progressive, morally opposed to slavery and friendly to a host of reform movements. His sole work of book-length non-fiction was a boys’ biography of Ulysses S. Grant, which got him invited to Grant’s inauguration following the 1868 election. He served a term in the Massachusetts legislature, and he was an advocate for public education and vocational schools. His fiction can sound condescending to modern ears—some of the dialect passages in his books border on the unforgivable—but his heart is always in the right place: despite our differences we’re all human beings of equal worth.

He had some peculiarities. He traveled widely and often, and his travel stories (Down the Rhine, Up the Baltic, Across India, Asiatic Breezes, etc.) all drew from personal experience. But in the age of the transcontinental railroad, he was mysteriously indifferent to the American west. He seldom mentioned it (except to object to Grant’s maxim that “the only good Indian is a dead Indian”), and even his so-called Great Western series never gets past Detroit, at which point the hero turns around and heads for (inevitably) Massachusetts. The third volume of the Great Western series is subtitled “Yachting Off the Atlantic Coast.”

And I won’t delve into the idea he espoused in his novel The Way of the World, that every public library should have a bowling alley in the basement…

Optic was hurt by Louisa May Alcott’s dig, and some of his later books lean away from the gaudy adventures of the Army-Navy series. Recently a few of his more tepid titles have been brought back into print by Christian presses—perhaps ironically, given that during his lifetime he was denounced from the pulpit as often as he was endorsed from it.

He wasn’t a great writer in the absolute sense, but nothing he wrote was less than endearing. The encomium to L. Frank Baum in the movie The Wizard of Oz applies equally to Oliver Optic: for years his work gave faithful service to the young in heart, and time has been powerless to put its kindly philosophy out of fashion.

His death in 1897 was reported in every major paper including the New York Times. I hope Julian Comstock plays some small part in keeping his memory alive.

Robert Charles Wilson

is the author of the Hugo-winning novel

Spin

. His new novel,

Julian Comstock: A Story of 22nd Century America

, is available now from Tor Books. You can read excerpts from his book

here

.

What an excellent and intriguing post. I just looked at manybooks.net and found a whole lot of Optic’s books available. I’ll download them right away. I just wish I could also download Julian Comstock for my Sony Reader right away… Sigh. Maybe Tor will open an ebook store soon and get all my money.

(Aside to Pablo: with lots of Gene Wolfe as well, please.)

What an interesting guy! His books sound joyously fun–thanks for bringing them to my attention!

I remember that Alcott passage!

Alcott’s jibe — “Is it natural for lads from fifteen to eighteen to command ships, defeat pirates, outwit smugglers, and so cover themselves with glory, that Admiral Farragut invites them to dinner?” — is interesting in the context of its time, because while it may not have been “natural” for young boys to have outrageous adventures, it wasn’t entirely the stuff of fantasy. Alcott was assuming that her readers knew that the Admiral Farragut in question, David Farragut, commanded a prize ship in the War of 1812 when he himself was only twelve. Farragut had further naval adventures before reaching adulthood, including being captured by the British off the coast of Chile and held prisoner for two years. It all sounds like something out of a boys’ adventure story, and it all actually happened. The nineteenth century was like that.

Farragut went on to be the dominant personality in the United States Navy for the next half-century. He commanded naval vessels in the war with Mexico and the Civil War; he was a pallbearer at Lincoln’s funeral; and he was promoted to full admiral in 1866, the first American to achieve that rank. His life was one of those exercises in earnest strenuousness that typify his era. Popular nineteenth-century writers like “Oliver Optic” start seeming a little less fantastic and a little more realistic the more one learns of the real history–and of the extravagantly sentimental, staggeringly energetic people–of their time.

Exactly! Optic made the same defense: he had met more than a few 17-year-old veterans who distinguished themselves in the war.

I almost fell out of my chair when I saw your post about Oliver Optic in my reader! I adore his books. I own a few of the ones you’ve pictured (and some you haven’t).

Good, someone came up with a better example than mine to counter Alcott. I just looked up the first well known sailor I could think of, Nelson, and found that he had his own command by 20. He was in service for 7 years before that, so he could very well have done something notable ( like command a prize ship ) had the need come up.

Was she that unaware of how young some men and boys were that were called to die for their countries, both in her own time and earlier?

mobileread.com has free custom versions of public domain ebooks. It only has two Oliver Optic titles: Watch and Wait (Illustrated) and A Lieutenant at Eighteen.

There are LOTS of free Oliver Optic books at Manybooks.net, all of them by Distributed Proofreaders, I believe. I helped with the proofing.

Adams loved boats. Sailboats, in particular, though some of his books feature steamers. If you like boats, you might like his books. Try The Yacht Club, or, The Young Boatbuilder.

I have been corresponding off and on with the author. I just bought his JULIAN COMSTOCK and my heart skipped a beat when I read the Dedication. I am thrilled to think that there are fans of Oliver Optic still walking the earth.

If any of you are interested you might check this out:

http://www.oliver-optic.com

You might be surprised . . .

Does anyone know where I can find (or examine) a copy of 1887 adult book, “The Voyage of Life: An Allegory”?

Queen Lili’uokalani had the pleasure of meeting Adams at a family gathering in Boston in 1896…she was delighted by his wit and humor. I would not have learned of “Oliver Optic” if it hadn’t been for her affectionate reference to him in her memoirs.